In Memoriam – George E. Smith, Co-Inventor of the Charge-Coupled Device

If you have ever taken a selfie on your smartphone or gotten an X-Ray from your doctor or dentist, you have George E. Smith to thank.

Smith, together with his close Bell Labs colleague and friend Willard S. Boyle, invented the charge-coupled device (CCD), revolutionizing the fields of imaging and digital sensing technology. Their invention provided an essential component for nearly every telescope, medical scanner and camera in use today. It allowed scientists to see the universe, and the depths of the oceans, far more clearly. And it empowered the rest of us to easily capture the everyday moments of our lives.

Smith, a Nobel Prize-winning Bell Labs physicist, passed away on May 28 at his home in Barnegat Township, New Jersey. He was 95.

Smith was born in White Plains, New York and served in the U.S. Navy before earning his B.S. from the University of Pennsylvania in 1955 and his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in 1959. His eight-page dissertation on the electronic properties of semimetals was, at the time, the shortest Ph.D. dissertation in the history of the university.

From there he was off to join Bell Labs in Murray Hill, New Jersey, where he would remain until his retirement in 1986. And it was at Bell Labs where he achieved his greatest breakthrough.

As with other iconic Bell Labs inventions, Smith and Boyle made their seminal discovery while pursuing a totally different agenda. They were working on semiconductor integrated circuits and trying to create better memory storage for computers when they came up with the idea for the CCD. They thought a solution could be found in the photoelectric effect — which Albert Einstein had explained and for which he won the 1921 Nobel Prize.

Channeling the collaborative Bell Labs spirit, they came up with the concept and design of a device that could transform light into electric signals – all in less than an hour of brainstorming in October 1969.

By converting photons to electrons, a CCD sensor could break image elements into pixels. As a result, the CCD provided the first practical way to let a light-sensitive silicon chip store an image and then digitize it. Light could now be captured electronically instead of on film, enabling the recording, storage and manipulation of images with unprecedented ease and precision.

The CCD technology soon found applications far beyond its original scope—from enabling high-resolution telescopes that expanded our understanding of the cosmos to medical imaging devices that improved diagnostic and surgical capabilities. And ultimately it evolved into an indispensable component of consumer electronics that put powerful cameras into the hands of billions worldwide.

The device, smaller than a dime, became ubiquitous. It is the eye behind every picture on the Internet, every digital and video camera, every computer scanner and copier machine. It quickly became the primary technology used for digital imagery and the sensor of choice in a wide range of devices.

It also proved critical to the development of robotics and autonomous cars and had multiple applications in defense and security. It proved particularly useful in astronomy research and is included, for instance, in the Hubble Space Telescope.

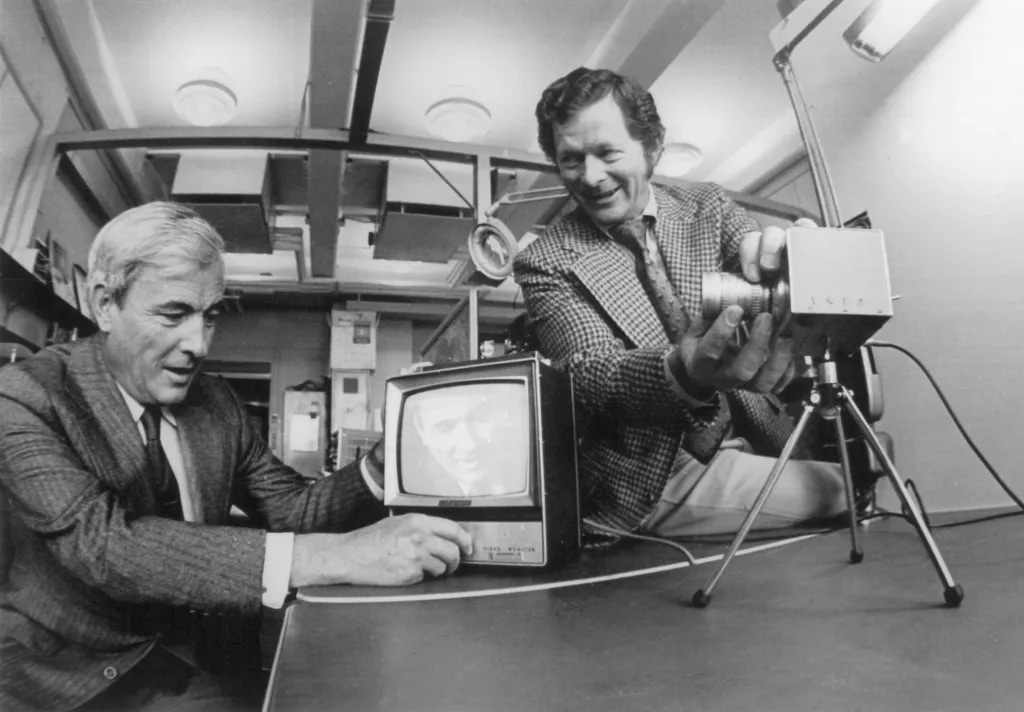

Willard S. Boyle (left) and George E. Smith (right), winners of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physics for the invention of the charge-coupled device.

The CCD marked a watershed moment in science and technology and earned Smith and Boyle a long string of accolades, culminating with the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physics. (They split the award with Charles K. Kao, who was recognized for work that resulted in the development of fiber-optic cables).

In announcing the award, the Nobel committee credited the CCD with helping build “the foundation to our modern information society.”

The CCD was just one of the 30 patents Smith held, and he was eventually inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Beyond their famous scientific collaboration, Smith and Boyle were also close friends and avid sailors who took many trips together. Boyle himself passed away in 2011.

Sailing was also a passion Smith shared with his wife Janet and the two would often sail on weekends until her death in 1975. Following his retirement, Smith sailed around the world with his life partner Janet Murphy for 17 years, crossing the Atlantic Ocean twice and sailing through the Panama Canal. Together they explored far-flung locations like the Galápagos Islands, Tahiti and the Cook Islands. They spent years sailing around New Zealand, Australia, Fiji, Tonga and Samoa, visited Indonesia and Thailand, and finally crossed the Indian Ocean and the Red and Mediterranean Seas before returning to New Jersey in 2003.

Smith is survived by three children, five grandchildren, seven great-grandchildren and a vast community of innovators who continue to build on his remarkable legacy. He will be sorely missed.